Emotions are adaptive and behavioral physiological response patterns to environmental stimuli. These patterns are malleable, transient, and can be regulated. The goal of regulating, or controlling, emotions is simply to obtain and maintain preferable emotional states and ending emotional states which are detrimental to your physical well-being, and social standing (Wadlinger, H. A., & Isaacowitz, D. M. (2012, February 1). Fixing our Focus: Training attention to regulate emotion.).

We base our emotions on our perceptions of our environment, and then we externally express those emotions in varying ways. Some expressions of emotion are rational, some are irrational. When something makes us angry, the irrational person who has no control over their emotions tends to lash out in very loud and boisterous ways. When we experience positive emotions, we express that with affection, laughter, or another appropriate affect.

Rationality vs. Reason

As a species which is capable of thought, and self-interest, we like to believe that we behave rationally. However, behavioral game theory has painted a different picture. The Ultimatum Game uncovered violations we’ve committed in assumptions of rationality. (Behavioral Game Theor. (n.d.). Retrieved from Behavioral Economics).

When we say words like Rational and Irrational, we tend to equate them with Reasonable and Unreasonable, respectively. Afterall, linguistically speaking, they are synonymous with each other, and Webster uses each in some way to define the other (Webster’s New Riverside University Dictionary. (1984). The Riverside Publishing Company) (Guralnik, D. B. (1987). Webster’s New World Dictionary Of the American Language (Warner Books Paperback Edition ed.). New York: Warner Books.).

- Rational: having or exercising the ability to reason; consistent with or based on reason

- Reasonable: rational; governed by or in accordance with sound thinking

- Irrational: the term used, usually pejoratively, to describe thinking and actions that are, or appear to be, less useful, or more illogical than other more rational alternatives.

- Unreasonable: Not reasonable or rational

In fields of psychological study, however, reason and rationality sometime miss each other a bit. The Ultimatum Game has highlighted a perfect example of this. The way the game works is simple:

- There are 2 players

- Player One is given a sum of money

- Player One is then instructed to give a portion of that sum of money to Player Two.

- Player Two then makes the decision to either accept or decline that sum of money.

- If Player Two accepts the sum of money, then both players get to keep the money they each have.

- If Player Two declines the money given them by Player One, then neither player gets to keep the money they were given.

- One variation goes further where Player One is given a menial task which requires them to earn the money, they are given to start the game.

In the variation of the Ultimatum game where Player One has to earn the money they then split between Players One and Two, Player One is generally more conservative with the portion given to Player Two. In either case, where Player Two feels the split between the two sums is not fair, Player Two declines their share of the money more often than not.

This shows a natural aversion to unfairness and inequality. While an aversion to unfair terms is reasonable to most people, in situations like the Ultimatum Game, it’s completely irrational.

This study showed that it didn’t matter if Player One gave Player Two more or less money than they themselves kept, if the difference was too heavily in one player’s favor over the other, more often than not, Player Two took the route of a lose/lose situation.

| Win-Win | Lose-Win |

| Lose-Lose | Win-Lose |

In Win-Win outcomes, both players feel like they’ve won. In negotiation terms, this means that each party gave up something so that each could come out ahead. With the Ultimatum Game, even if Player One split the money 70/30 in their favor, if Player Two accepts this split, it’s a win-win because both players come out with money in their pocket.

In lose-lose situations, which is the route most often taken by Player Two, both parties lose altogether. As irrational as this is, the inequality of a 70/30 split is often too much for Player Two to accept.

We tend to see the rational train of thought as the reasonable, and demand that the world exists on some spectrum of what defines fair. Unfortunately, the feeling of something being fair is emotionally based, as is most of our decision-making processes. As humans we are highly susceptible to our emotions. When we’re faced with challenging situations, we tend to lean toward the irrational even more so than rational choices.

Our emotions are the basis for our actions. Externally behaving irrationally can cause us to lose social standing with our peers, alienate our significant others, or force a lose-lose situation over the more desirable win-win just to avoid a little inequality.

However, it’s a fact of life that none of us can escape: Inequality and Unfairness exists, and we must manage that. While we have no control over whether the frog eats the snake or the snake eats the frog, we do have control over how we react emotionally, and how we express those emotions externally.

The Rational Equation

There is an appointed time for everything, and a time for every affair under the heavens… A time to love, and a time to hate; a time of war, and a time of peace.

New America Bible: Ecclesiastes

Despite how you feel about the origination of this particular quote, the fact of the matter is that it holds a solid place in our society because it’s true. It’s also the basis for rational and irrational thoughts and actions.

You’ve heard one of your parents, grandparents, or maybe a teacher or the parent of a friend say some variation of this to you at one point in your life. The lesson is clear. There is a time and place for every action and thought. The weekly Wal-Mart grocery trip is not the time or place to throw a tantrum. Standing in front of your teacher the day a project is due is not the time or place to try to start your work on that project.

When it comes to an externally expressed emotion being seen as rational or irrational, it often comes down to time and place, but intensity also matters.

(Time and Place) Intensity or Volume as expressed by avenue of action = Rational or Irrational

You go out to dinner with your significant other. Two tables over a man begins yelling and screaming at the server, so much so that his face has turned red and you believe steam will roll out of his ears any second.

The man is upset because he asked for his steak to be served medium rare, and the steak brought to his table is closer to medium. Obviously, this is a small issue that can be easily fixed. Within most restaurants, all you typically have to do is send the steak back and they happily correct the mistake. It’s an easy one to make, and simple one to fix.

But, the man two tables over doesn’t want to give his server the opportunity to return with another steak correctly cooked because the restaurant is busy, and he simply doesn’t want to wait for his meal again. His feelings on the issue are understandable, perhaps even reasonable.

His reaction is completely irrational.

A busy restaurant, no matter the issue, is not a place to yell and scream at the top of your lungs. It’s very likely not the right time either. If he’s at the restaurant on business or with his in-laws, then his violent reaction will likely elicit some form of alienation in his personal or professional life.

Now let’s address his temper tantrum. This goes to volume and expression. He’s angry. That’s understandable. However, outward expression of anger is not usually socially acceptable. Not only is it loud and disruptive, it’s threatening.

In this situation, the equation would look something like this.

(Family or business meeting + Busy Restaurant) Losing his temper with loud and threatening behavior – Irrational reaction

What about the server, other patrons, or restaurant manager?

The server reacts by taking a step back from the very angry and threatening man. He apologizes for the mistake and leaves the immediate area to get the manager.

This is a completely rational and reasonable reaction. The server’s emotions are likely going full blast at this moment, and his fight or flight reaction is likely off the charts. However, he composes himself, maintains personal control of how his emotions are expressed externally, and does what he’s supposed to do in a challenging situation like this: He gets the manager.

The primary difference, beyond the obvious roles being played, between the angry patron and the server is each one’s ability to control his emotions, and how they’re expressed.

Control and Regulation

When we see, hear, or use the word control, we tend to think of the ability to exert authority or influence, or in some way restrain. A broader meaning of the word control however means to “harness” or to “regulate.” So, going forward, rather than framing what you’re doing as learning to control your emotions, frame your thoughts around regulating your emotions.

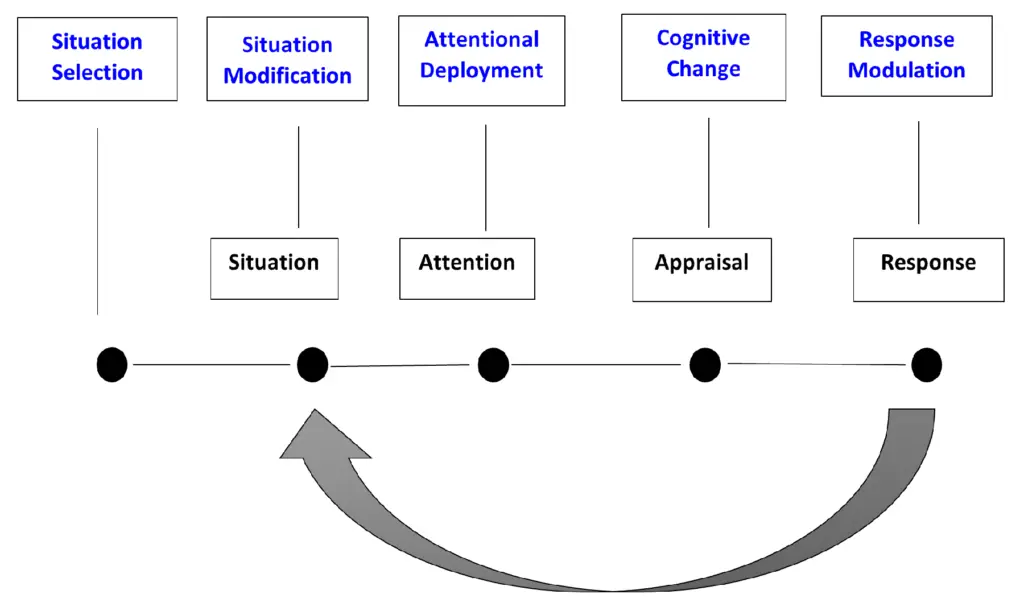

There are 5 Families of emotion regulation (Gross, J. J. (2015). Handbook of Emotion Regulation. Guilford Publications Inc.)

- Situation Selection

- Situation Modification

- Attentional Deployment

- Cognitive Change

- Response Modulation

When faced with a challenging situation, you may turn to one family of emotional regulation or another depending on where you’re at within the situation. If you attempt to avoid the challenging situation all together because you know it will impact your emotions adversely, you’re deploying Situation Selection.

If, after the challenging situation has come to a close, and you are reflecting on it as a past action and choose to change how you feel or what you think about the situation, you would be deploying Response Modulation.

Emotions unfold over a series of different steps, and simply choosing a method of emotional control isn’t as simple as that. You may be faced with the first 4 families of emotional regulation congruently, or in successive order so quick that you can’t recognize the steps before the situation is done and passed.

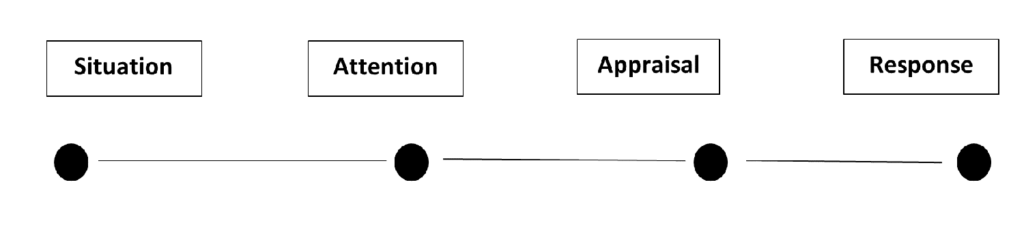

In his Modal Model of Emotion, Dr. James J. Gross best explains that our emotions arise in the context of an instance where you directly interact with a situation. That interaction gives rise to a malleable and coordinated response system.

The situation-attention-appraisal-response sequence begins with an external and physically relevant situation as it pertains to you. You then devote your attention to certain variables and begin an appraisal of those variables. Your appraisals of the variables that were so important as to elicit your attention and focus then form your response.

Your response will involve changes in your experience of the situation, your externally expressed behaviors, and how you react physiologically such as with fluctuations in your heart rate or blood pressure. Your response will then trigger another change in the situation either for yourself or those within your immediate environment.

Going back to that irate customer at the restaurant, look at how his behavior impacted the server, and how it might have impacted your behavior if you were actually there. His irrational loss of composure would likely have had an impact on your emotional triggers. You, as a result, would then find yourself sharing in this challenging situation in how you react and respond.

From this point, you’re already affected and so are past Situation Selection. You can choose to deploy any or all of the other families of emotional regulation and control from that point on.

As already discussed, Situation Selection involves making a conscious choice as to which situation you allow yourself to enter based on how you believe it will affect you emotionally. This sounds preferable if you follow the idea that the best time to avoid a catastrophe is to prepare for it before it arrives.

However, knowing how any given situation will affect you requires an astounding level of honesty where your past actions are concerned. There is a profound gap between our experiences and how we remember them (Gross, J. J. (2015). Handbook of Emotion Regulation. Guilford Publications Inc.).

Situation Modification is an option for situations where you can change what’s actually going on. In the case of the irate diner, you won’t have much control over him or the server. However, in another example, if you’ve planned a big family cook-out at your house complete with a grill menu, only to wake up and discover over cast, you might change your plan of action rather than cancel the gathering all together. This change might be to serve spaghetti, a common family favorite, around the dinner table, rather than grilled hamburgers and hot dogs.

Where the change in weather would also affect you emotionally, situation modification also includes finding a way to look at the weather as a positive rather than a negative internally as well as your external expression of adjusting your plans to match the day.

Attentional Deployment would involve your choosing to deploy something like an internal distraction. In the restaurant, you may choose to distract yourself with your company rather than giving the angry man any of your attention. You would essentially find a way to ignore the situation at hand.

Cognitive change allows you to alter the amount of attention you provide the situation at hand. In any challenging situation, the variables that effect you emotionally are the variables to which you provide your attention and focus.

In the case of your cook-out getting rained out, you can choose to deny the rain any of your attention, and simply focus on the presence of family. In this case, the presence of your family, which was your intended desire, gets all of your attention and therefore has the primary effect on your emotions.

Response modulation occurs late in the process of generating emotions and refers to your response to the situation.

With your cook-out, you chose to deploy situation modification early on in the day and situation. After the family have eaten your spaghetti dinner and left you can continue with this track by focusing on the success of the day or return to your initial interaction with this situation by focusing on the fact that it rained the whole day. Response modulation is the phase where you choose how to react, and what to react to.

In choosing how to react, you can deploy stress relieving techniques such as intense exercise or a bubble bath. In choosing what to react to you can ruminate on how happy you were to see your family, or on the fact that no one got to have cheeseburgers. It’s your choice.

Taking Responsibility

The perception of true and absolute control is nothing more than an illusion at best. Conspiracy theorists like to tell us that the New World Order and its cabal are working through our banking systems, news organizations, and historical institutions so that they can exert secret and authoritarian control over the lives of the masses world-wide, do away with sovereign nations, and eliminate personal rights.

In some of these theories, the likes of the Rothschild, Dukes, Kochs, Astors, and Rockefellers are the ruling elite who seek to control the daily lives of ordinary citizens, and in the end, a democracy is nothing more than an illusion.

This may be true, and it may be complete lunacy. Rational thought tells us that while accepting and allowing for the possibility of this eventuality is reasonable, obsessing over it is completely irrational. Let’s face it, if the Rockefellers and Astors want to obtain worldwide dominion and rule over the masses, they will. What can you do about it personally, as an individual lone person?

An asteroid killed off the dinosaurs. They were the ruling class of this planet just eating trees and such before a giant asteroid came along and smacked them out of existence. If that happens again, what can you do about it?

Yea, these scenarios are extreme, but the point here needs to be illustrated. You have about as much control over the goals, aspirations, and possible evil doings of the 1% as you do an asteroid that may or may not collide with earth in 2236.

For those of you who have grown children, as much as you love your children and as much as you try to help them, how much control do you actually have over their adult lives?

Control is an Illusion

- You cannot control what happens tomorrow on a large scale.

- You cannot control when and where a natural disaster will occur.

- You can’t control whether or not you get a peaceful meal in a nice restaurant when an angry man dislikes how his steak is cooked.

Responsibility is Real

You do, however, have complete and total jurisdiction over how you behave.

When you’re faced with an angry man in a restaurant, you can choose to react irrationally, or take responsibility for your emotions and personal situations.

- You can ask for the check and leave, punishing your server for a patron’s bad behavior by refusing to tip.

- You can turn to the person or people you are sharing a meal with, make a joke, and go on about your social event.

- You can ask for the check, leave your server a huge tip, and go on about your evening

- You can leave the restaurant fuming about the angry patron, perpetuating those feelings of hostility and imposing them onto your family

- You can leave the restaurant and choose to go home or to the movies with a good attitude, refusing to allow someone else’s bad attitude to affect you.

Your response to any challenging situation is yours and yours alone. Take responsibility for that because that’s the most powerful tool you have in your arsenal. Control over external factors has nothing to do with any of this.

Controlling your emotions internally, and how you express them externally is your responsibility, and it’s important that you take responsibility for them.

How To Take Responsibility For Your Emotions

How do you take responsibility for your emotions? It should be easy to obtain and maintain control over something so fundamental, but there are a few factors to consider.

Attempting to control your emotions in a highly charged situation is not the time or place to begin trying. The best time to learn a skill is before you will need it. The best time to prepare for a disaster is before it happens. The best time to derail a tragedy is to put preventive measures in place before a situation becomes too out of hand.

Get To Know Yourself

Understanding your personal history and character is key. You need to develop an understanding of who you are under the face you show the world. You can get a glimpse of your character by asking the people who know you best to help you with this task. You can also get to know yourself a little better with mindful meditation.

Most people hear or read the word meditation and either move past it like it’s a crazy thing, or they think about long hours of sitting still trying to empty their minds. That’s not what mindful meditation is. The practice of mindful meditation is simple. The goal isn’t to empty your mind, it’s to recognize that your mind has wandered during a moment of silence and peace and paying attention to what it’s wandered to.

The largest benefit of mindful meditation has been found to be that moment when you realize that your mind has wandered, and you return to focusing on your breath. It’s as simple as that. The benefits of mindful meditation include improved focus during tasks, and that it can help you to develop a better intrapersonal relationship with yourself.

Understand Your Personal Story

We all have a story. Some stories are sad, and some are awesome. Understanding your past, and how it has shaped you is important in recognizing and understanding your emotional triggers.

Once you come to understand yourself and your emotional triggers, you can practice and develop positive and patterned responses to stimuli in difficult and challenging situations.

Your story will dictate your emotional triggers because your emotions are patterned responses. We don’t’ develop patterned responses in a vacuum. They come about from the collective long-term history of our past. This is how childhood shapes and molds us.

Remember, you have no control over asteroids or Rockefellers just like you have no control over your childhood or past. You do have control over how you allow these variables to affect you going forward, and you have to take responsibility for this control in order to regulate your emotions in challenging situations.

The Real Picture of Emotional Control

We each face challenging situations every day. Some of us come face to face with our own mortality on a daily basis as a reality of a profession. Firefighters know that jumping into that truck may be the last sane thing they do should something go horribly wrong in a situation where something’s already gone bad. Explosive experts know that some decisions carry the consequence of life and death.

Soldiers know that re-enlisting can mean deployment to a theater they may not come back from, and what’s more, military spouses know what they’re in for when they remain in a marriage deployment after deployment. You may face a boss whose default setting is irate, or a child whose main focus for the moment is pushing your buttons and challenging your sanity at every turn.

Every moment of every day we are faced with any number of situations that will elicit variable emotional reactions. In overly challenging situations, the difference between keeping a job that pays your mortgage and child’s tuition and losing it may be your ability to regulate your emotions.

Learning to control your emotions starts with an understanding of what emotional control really is: regulation over the experience and expression of emotional states.

The next step to controlling your emotions is understanding yourself. Spend some time with your inner voice, develop a healthy intrapersonal relationship. We all like our social structures and spending time with our significant others, but you should be able to spend time alone without being lonely. Go for a walk, spend some time meditating. Do any number of things that allows you to focus on your inner-self. Once you’ve started this, it’s time to work on what kind of a personality your inner-self is.

Listen to that voice you hear any time you work through a task. That’s your inner-self. If you hear that voice telling you things like “you’re a bad person,” then it’s time to challenge these statements. Self-talk is helpful to completing tasks, learning new skills, and learning to control your emotions, but that self-talk absolutely must be positive for it to have the desired effect.

Once you can talk yourself through a task without destroying your self-esteem, it’s time for some inner reflection in your past experiences to identify your emotional triggers.

- What past events have triggered positive and negative emotions?

- What was it about those events that are most memorable?

Your emotional triggers can be anything from hearing a certain instrument to reading a blog. Adults who played an instrument in school often find their emotions of joy or elation triggered when they hear that instrument being played in any setting as an adult. Adults who heard the same negative phrase over and over as a child from their parents or other adults they respected may feel those same feelings of shame or defeat when someone else uses them in a different context later.

When you know what triggers your emotions and why, you can begin working on developing healthy ways of externally expressing those emotions in healthy and positive ways. There are a number of methods commonly deployed in dealing with negative or scary emotions. One such method is Cognitive Reappraisal. This involves addressing the negative emotion, and purposely changing its context or your view of the context so that its emotional impact is also changed.

Another method is Expressive Suppression. This form of response modulation requires that you inhibit your expression of a given emotion. There a physiological side effects of this though, because people who do this will more often experience spike in blood pressure or something similar when they hold it in.

No matter how you choose to express the positive and negative emotions you feel, if you want to be able to regulate your emotions on a meaningful level in challenging situations you have to first understand the emotions, why you’re feeling them, how you’ve reacted in the past, and what their corresponding consequences were. By understanding this, like with any equation, you can use what you know and learn to map out the responses you deem appropriate, and then practice them.

Have you ever noticed that you react less drastically to situations where you were expecting a certain thing to happen? That’s because when you expect a certain chain of events to unfold in specific ways your inner voice starts preparing you for those eventualities. When events unfold in the way you expect, you aren’t surprised. You’re prepared.

However, when something happens that you weren’t prepared for you experience a feeling of not knowing what’s going on. This is why you practice your emotional reactions after you’ve mapped out acceptable responses.

Granted, we can never plan for every eventuality, and continually talking to yourself in the mirror will get tiresome, for yourself and others. One life skill that helps with this is resilience. Work on ways to develop your resilience so that when you’re faced with a challenging situation, you’re already in a place you’re somewhat familiar with.

Control is an illusion but regulating your emotions in challenging situations is the one way you can control how you react to a world full of amazing possibilities. Taking the time to address your need to develop positive external expressions of your emotion, and internal experiences of emotion allows you better control over what does and does not ultimately affect you.